Tenant Farming in Arkansas

Arkansas Delta: Early Years

Today the Mississippi River Delta is one of the most fertile agricultural regions in the world, but this has not always been the case. For thousands of years, the Arkansas region of the Delta was nothing but swamps and forests. Early European settlers were hunters, trappers and fur traders. Early in the 19th century, settlers began arriving in the Delta from other states, such as Kentucky and Tennessee. They cleared forests, drained swamps and expanded cotton production into the new region. Though the river brought rich soil to the region, it often took back its gifts during periodic flooding that wiped out many farmers. Today the fertile Arkansas Delta also produces rice, soybeans and other crops in abundance.

Today the Mississippi River Delta is one of the most fertile agricultural regions in the world, but this has not always been the case. For thousands of years, the Arkansas region of the Delta was nothing but swamps and forests. Early European settlers were hunters, trappers and fur traders. Early in the 19th century, settlers began arriving in the Delta from other states, such as Kentucky and Tennessee. They cleared forests, drained swamps and expanded cotton production into the new region. Though the river brought rich soil to the region, it often took back its gifts during periodic flooding that wiped out many farmers. Today the fertile Arkansas Delta also produces rice, soybeans and other crops in abundance.

Pre-Civil War: Enslaved Labor

Cotton became a staple in the Delta soon after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. By the time Arkansas achieved statehood in 1836, Delta planters had established a cotton kingdom borne on the backs of enslaved laborers. After the Civil War, southern planters faced the prospect of regaining control of lost land and labor to farm it. Day laborers and tenant farmers replaced slaves as the source of agricultural labor. Both black and white farm workers under this new system often found themselves in situations that weren’t much better than slavery.

Cotton became a staple in the Delta soon after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. By the time Arkansas achieved statehood in 1836, Delta planters had established a cotton kingdom borne on the backs of enslaved laborers. After the Civil War, southern planters faced the prospect of regaining control of lost land and labor to farm it. Day laborers and tenant farmers replaced slaves as the source of agricultural labor. Both black and white farm workers under this new system often found themselves in situations that weren’t much better than slavery.

Tenant Farming Labor System

Tenant farming, which replaced the slave-based agricultural system in the south, enabled farm laborers to rent ground from landowners for a percentage of crops (called crop rent) or cash payments (called cash rent). Terms of contracts varied, dependent on whether the laborer owned any equipment or purchased his own seed and supplies. Crop rent contracts generally required that one-fourth to one-third of the crop be paid to the landlord. Sharecroppers, at the lowest rung of tenant farming, lacked equipment and capital, which had to be provided by landlords. Thus, they received a smaller percentage of crops, typically 50%.

Tenant farming, which replaced the slave-based agricultural system in the south, enabled farm laborers to rent ground from landowners for a percentage of crops (called crop rent) or cash payments (called cash rent). Terms of contracts varied, dependent on whether the laborer owned any equipment or purchased his own seed and supplies. Crop rent contracts generally required that one-fourth to one-third of the crop be paid to the landlord. Sharecroppers, at the lowest rung of tenant farming, lacked equipment and capital, which had to be provided by landlords. Thus, they received a smaller percentage of crops, typically 50%.

Hard Times for Farmers

The stock market crash of 1929 brought ruin to rich and poor throughout the Delta. Tenant farmers found themselves in dire straits. Bank closings shut off financing for many Delta farmers. Crop prices plunged, as need for raw materials declined. During the Great Depression, federal inspectors described tenant farmer existence as a “picture of squalor, filth, and poverty.” Hard times in the rural South brought laborers and tenant farmers together into various associations during the late 1800s. Groups such as the Agricultural Wheel sought to improve financial conditions for members.

The stock market crash of 1929 brought ruin to rich and poor throughout the Delta. Tenant farmers found themselves in dire straits. Bank closings shut off financing for many Delta farmers. Crop prices plunged, as need for raw materials declined. During the Great Depression, federal inspectors described tenant farmer existence as a “picture of squalor, filth, and poverty.” Hard times in the rural South brought laborers and tenant farmers together into various associations during the late 1800s. Groups such as the Agricultural Wheel sought to improve financial conditions for members.

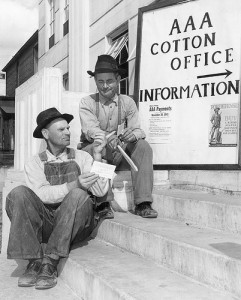

The Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 was passed to help support cotton prices by reducing production. Government support checks were paid to farmers to offset the loss of income, due to plowed up cotton. Checks were made payable only to landowners, who were supposed to share income with tenants. Many did not, however, and abuse was widespread. With less land in cotton production, the need for tenant farmers was reduced. Some tenant farmers had the option of eviction or becoming day labors, who were not eligible for support payments. Tenant farmers searching for ways to improve their miserable living conditions turned for help to two Tyronza businessmen, H. L. Mitchell and Clay East.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 was passed to help support cotton prices by reducing production. Government support checks were paid to farmers to offset the loss of income, due to plowed up cotton. Checks were made payable only to landowners, who were supposed to share income with tenants. Many did not, however, and abuse was widespread. With less land in cotton production, the need for tenant farmers was reduced. Some tenant farmers had the option of eviction or becoming day labors, who were not eligible for support payments. Tenant farmers searching for ways to improve their miserable living conditions turned for help to two Tyronza businessmen, H. L. Mitchell and Clay East.

Southern Tenant Farmers Union

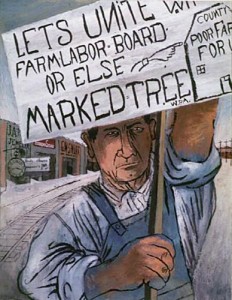

With leadership from H. L. Mitchell and Clay East, 11 white men and seven black men met in a small schoolhouse near Tyronza in July 1934 and formed a union.  Much of the union’s historic importance came from the fact that it included both black and white tenant farmers as members and leaders.

Much of the union’s historic importance came from the fact that it included both black and white tenant farmers as members and leaders.  Women were also welcomed into leadership ranks. This integration was rare at that time and place. The union used such means as strikes, demonstrations, and rallies to call attention to their plight. Often, their efforts were met with intimidation and violence. Efforts to destroy the STFU included eviction of tenants and firing farm laborers who joined. Union leaders received many pleas for help from evicted tenants and interceded on their behalf.

Women were also welcomed into leadership ranks. This integration was rare at that time and place. The union used such means as strikes, demonstrations, and rallies to call attention to their plight. Often, their efforts were met with intimidation and violence. Efforts to destroy the STFU included eviction of tenants and firing farm laborers who joined. Union leaders received many pleas for help from evicted tenants and interceded on their behalf.

The Union’s Legacy

Union expansion beyond Arkansas brought many locals to Oklahoma, Missouri and Mississippi. The STFU also helped support strikes by fruit canners in California and cane harvesters in Louisiana. By the 1940s, however, membership in the Southern Tenant Farmers union began to decline. The decline was accelerated by the loss of workers to northern industries gearing up for World War II. By the 1960s the STFU ceased to exist. Social and political writer Michael Harrington perhaps best expressed its legacy:

“ In one sense the Southern Tenant Farmers Union . . . was defeated, and there is no use trying to walk around the fact. But in that defeat, pressure was generated which left its mark on American history.”

Though it slipped quietly out of existence, it provided a lasting legacy of integrated, non-violent protests that would be carried on into the labor and Civil Rights movements of the coming decades.